I’ve always wanted to see a California condor in the wild. It’s on a list I keep in my head of animals I’d like to glimpse in their natural habitats, which includes, in no particular order, a male moose with full antlers, a whale, a ringtailed cat, a hedgehog, a swarm of monarch butterflies, and any kind of monkey. But the California condor stands out because it came so close to extinction. When I was a kid, there were only nine wild condors left. At that point, in 1987, they were taken into captivity, and their future looked bleak. The idea that we could lose North America’s largest flying bird—a vulture with a wingspan of almost 10 feet—struck me as tragic even then.

Joy Lanzendorfer and Kelly Sorenson, Executive Director of the Ventana Wildlife Society, join Alta Live on Wednesday, April 21 at 12:30 p.m. Pacific time.

But we didn’t lose the condor. Thanks to conservation efforts, it has made a comeback. There are now around 300 condors in the wild, most living in Central and Southern California, with smaller populations in Arizona and Utah. I kept thinking about this throughout 2020, a year filled with environmental disasters, from wildfires to melting permafrost to a worldwide pandemic caused by a mutating virus. Even as climate change bears down and some scientists say we’re entering an era of mass extinction, the preservation of the California condor shows that we can repair some environmental damage. Not that it was easy. Despite extensive time and resources spent, the condor is still critically endangered. Lead poisoning remains a threat, and the bird’s future is far from guaranteed. So I’m not sure whether my interest comes from ecological hope or an urge to see a rare creature while I can.

Either way, on a cold morning last November, I drove to Pinnacles National Park, east of the Salinas Valley. In 2003, California condors were reintroduced into the park, and now it’s home to a fluctuating flock of around a hundred of them. Pinnacles is also one of the smallest national parks and, thanks to its proximity to San Francisco, often crowded. The last time I visited, it had been so full that I had to turn around at the entrance. This time, I snagged a parking space, shoehorning between vehicles near one of the trailheads, and asked a ranger where I could see a condor. “If you’re on the high peaks at daybreak or sunset, you might see one,” she said. “Otherwise, they sometimes hang out above the campground.”

This made it sound like I’d have more luck spotting a condor in the campground than after a strenuous hike to the park’s rocky peaks. Still, I started down the trail, through an oak and pine forest, leaves crunching underfoot, the air smelling like a Christmas wreath. Birds were everywhere—woodpeckers hammering on trees, towhees hopping toward mud puddles, a hawk piercing the quiet with its shrill call. I searched the sky for condors, which are capable of soaring as high as 15,000 feet and traveling 200 miles in a day. Instead, water dotted my face. It was raining. Discouraged, I gave up and turned around, unwilling to climb wet rocks. Condors are smart birds, I thought. They probably wouldn’t fly around in the rain anyway.

Walking back, I started encountering newly arrived people on the trail. First it was just a few hikers in rain slickers, then more and more—kids darting and laughing, older couples pumping walking sticks, young women in baseball caps jogging through the icy sprinkles. Apparently I’d beaten the rush. As I drove out of the park, visitors streamed from the front parking lot, despite the rain, despite the masks they wore for protection against the coronavirus. I wondered how many of them had come because, like me, they wanted to glimpse a condor.

High above, two black birds circled in the sky. I craned forward, gazing up through my windshield, but it was just crows. I should have known that seeing a condor wasn’t going to be so easy.

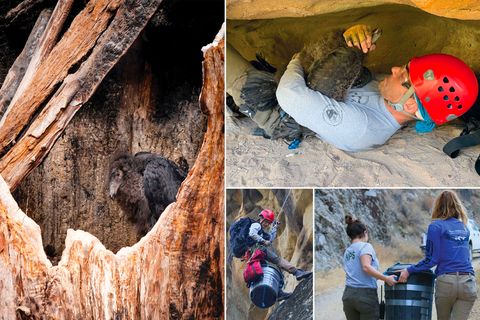

A week earlier, I’d joined a Zoom meeting held by Ventana Wildlife Society to learn how the Dolan Fire had affected wild condors. Since 1997, Ventana has been releasing captive-bred condors into the wild at its sanctuary in Big Sur. Having started at zero, the population in Central California reached 101 wild birds in 2019, including 8 nesting pairs—a flock that Ventana co-manages with Pinnacles. (Previously, Ventana also helped recover bald eagles, which are no longer endangered.) On August 20, while condors roosted nearby, flames came roaring through the sanctuary, burning the release pen and the research facility to the ground. In the aftermath, 11 birds were missing: 9 free-flying condors and 2 nestlings.

On Zoom, hundreds of people had joined to hear about the birds. They were especially interested in Iniko, a six-month-old nestling whose name means “born in troubled times.” Condors, which typically mate for life, lay a single egg high up on cliffs or in large trees. Iniko’s parents, Redwood Queen and Kingpin, had chosen a hollow in a redwood. The nest was fitted with a camera, which provided dramatic video of the fire: First, Iniko is shown in the far end of the nest looking out the cavity toward the woods. The camera follows the bird’s line of sight, scanning the hole. For a second, there’s only the ominous crackling of fire. Then, on the left side of the screen, a glow appears—the flames creeping up the tree. The bird’s wing flaps against the camera, and the footage ends.

The next morning, Iniko was alive, but her parents were gone. The tree was blackened and caved in. While Redwood Queen returned, Kingpin was presumed dead. With the dominant bird missing, another male, Ninja, decided to harass Iniko. There’s footage of this, too: Ninja lands on the nest, folding his wings so that they briefly make the shape of a heart, then stalks toward Iniko. He attacks, dust or ash rising around the birds. A moment later, Redwood Queen appears and joins the tussle. Then, suddenly, all three birds tumble from the nest.

Redwood Queen and Ninja managed to catch flight, but Iniko fell to the ground. While she survived, her leg was bruised. At that point, Ventana intervened and took her to the Los Angeles Zoo. She’ll be released with a new flock later this year. Redwood Queen will probably mate again, biologist Joe Burnett explained on the Zoom call. “Ironically, it could even end up being 729 [the number given to Ninja],” he said. “There’s all sorts of surprises that could come our way with condors.”

I was learning that condors are social birds with big personalities. Their individual bios on Ventana’s website read like Facebook profiles. Cosmo, an amorous female, has a story like “a television soap opera.” Wild 1, a “very feisty and dominant female,” is on her third mate, having left the other two. The Three Amigos, a trio of males, “went everywhere together” and had “some unsafe (and frankly, unintelligent) behaviors.” A large bird named Puff Daddy tries to make himself look bigger by inflating air sacs on his neck: “He just doesn’t seem to know how to deflate! We don’t think he’s fooling anyone.” Sadly, there are also accounts of the dangers condors face—they’re hit by cars, electrocuted, lost in fires, and, most often, poisoned by lead.

Although wildfire is a concern, the biggest threat to condors is lead toxicity from spent bullets, which rupture into tiny pieces when they hit a target. A condor only needs to eat a few fragments to be poisoned. Between 1992 and 2019, 93 wild condors across the West and Mexico died from ingesting lead.

“That’s a huge number,” says Kelly Sorenson, Ventana’s executive director. “No other mortality factor comes close to that.”

Hunting with lead bullets is banned in California, but the alternative, copper ammunition, can be difficult to find. Ventana has given away over $250,000 worth of copper ammo within the condors’ Central California range, especially to ranchers who manage ground squirrels and other pests by shooting them and leaving them in the field—a practice that hasn’t gone unnoticed by the condors.

“They hear the gunshots, and it’s like a dinner bell,” says Sorenson. “I think they go, ‘There’s a bunch of ground squirrels over there. Let’s check it out.’ ”

People often find vultures like condors repulsive. Not only is their diet gross to us, but the sight of vultures circling overhead is an unsettling reminder that death is nearby. In the book Flight Ways, about bird extinction, author Thom van Dooren describes the vulture as “a kind of liminal creature, inhabiting a space somehow strangely between life and death.” Since its role is to consume carrion, its corrosive stomach acid protects it from substances that would kill other animals. In this way, vultures turn death into life: by feeding primarily on cadavers, they themselves live.

Maybe it’s no coincidence, then, that the Grim Reaper’s black robes are reminiscent of vulture feathers. After all, vultures have been with us since ancient times. Condors were in North America before people. During the late Pleistocene, they soared over the entire United States, from California to Florida. By the time Lewis and Clark saw “a buzzard of the large kind” near the Columbia River in 1805, though, its range had shrunk to the West Coast, from British Columbia to Mexico and into the Southwest.

During the gold rush, there were tales of miners storing gold dust in the hollow shafts of condor feathers as a kind of carrying case. In the 50 years that followed, the number of condors dropped significantly. They were poisoned by lead bullets and strychnine-laced carcasses left out for predators. Later, when power lines went in, birds of all sorts were electrocuted, including condors. Chemicals like DDT in the water supply led to eggshell thinning. Habitat destruction, like the decimation of old-growth redwoods, didn’t help either.

On top of that, condors were frequently shot. Sometimes this was out of a misguided fear that they would carry off livestock or small children. Other people were impressed by the birds’ size and charisma and hunted them as trophies. One man, E.B. Towne, killed as many condors as he could, collecting at least 21 skins, according to the book Nine Feet from Tip to Tip: The California Condor Through History. As the birds’ population fell, demand for eggs went up among collectors. On June 22, 1900, a Kansas newspaper interviewed a man named Herbert M. Beesley, who scoured the High Sierra for condor nests. He hoped to make up to $1,500 an egg, equivalent to around $46,000 today.

An 1899 article in the San Francisco Call gives a heartbreaking account of condors trying to defend themselves against nest robbers. After two men steal a condor egg on a treacherous Santa Barbara cliff, the birds attempt to fight back, tearing at the men “with their murderous talons…. The attack was met with a series of blows.” In the end, the men beat the condors with rocks and clubs, seriously injuring them. The egg “became the sight of the town,” the article concludes unironically. “It is the only condor’s egg that has been found in that part of the c

ountry for many years.”

The last known California condor in the redwood forests of Humboldt County, where I grew up, was spotted in 1892 near Eureka, where it was shot and stuffed. Now, almost 130 years later, the Yurok Tribe, in partnership with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the National Park Service, is working to bring condors back to the area.

The condor is sacred to the Yurok—as well as many other tribes. The Yurok call the bird Prey-go-neesh, and it’s an important part of their World Renewal ceremonies, according to Tiana Williams-Claussen, director of the tribe’s wildlife department. The Yurok believe that their ceremonies go back to the beginning of time. One of the great creators came to all the spirits of the world and asked for a prayer to help guide the dance. Since condors don’t have voice boxes, Prey-go-neesh remained silent until the Creator asked him to sing. “And so he did,” Williams-Claussen says. “And the Creator’s like, ‘That was the most beautiful song that I’ve ever heard in my life.’ And in fact, he sang it back to Condor, and it was the most beautiful and powerful song that has ever been. And so we continue to use those songs in our renewal ceremonies to this day.”

The Yurok have long felt the absence of the condor: not only are its feathers part of their regalia, but it is a Yurok belief that a vital role of the bird is to carry prayers to the heavens. In her book Fathoms, author Rebecca Giggs writes that extinct species leave behind a kind of “haunting.” They “don’t just disappear, in a snap, but continue to be revealed after their passing,” she writes. Sometimes the hauntings are physical evidence, like the enormous tunnels in Brazil that many scientists believe were dug by ancient giant sloths. Other times, they’re reflected in human cultures. Consider New Zealand’s huia bird, which was driven to extinction in the early 1900s by a fashion craze for hats trimmed with its white-tipped tail feathers. As Giggs points out, the bird’s song was sung by Maori hunters long after its extinction. “Mimicry of the huia’s call passed from human generation to generation…. The dead bird’s tongue, spoken from our mouths.”

For the Yurok, whose purpose is tied to maintaining a balanced world, restoring the condor is part of larger efforts in “rebuilding our landscape, rebuilding our relationship with it, and rebuilding ourselves,” says Williams-Claussen. But releasing an endangered species into an area with a fraught environmental history is complicated. Tribal leaders and government officials have been meeting with landowners as far away as Sacramento and Portland, Oregon. There have also been negotiations with the timber industry, which fears the financial impact of a protected bird in its forests. If all hurdles are cleared, the Yurok are hoping to release condors into Humboldt County this fall.

In the meantime, the tribe is building release infrastructure to be installed on national park land. The exact location is a secret, since it’s important that wild condors be kept away from humans. (In the past, over-friendly condors have hopped into garages and, once, onto the general manager’s desk at the Sierra Mar restaurant in Big Sur.) When a condor is set free, it will be a “soft release.” The cage door will be slowly opened, and everyone will wait for the bird to fly away.

On November 19, I drove to Big Sur hoping to finally see a California condor. It was a beautiful day, the ocean glittering below the rugged mountains, as I followed Ventana wildlife biologist Stephanie Herrera to a pull-off along Highway 1 where condors are often spotted. As I got out of my car, sea lions were barking on the beach far below the steep ravine.

Herrera introduced me to Tim Huntington, a longtime Ventana volunteer. He was tracking the radio transmitter mounted to one of the condors released from Ventana with a tall antenna that looked like it belonged on the back of an RV. In a British accent, he said that right now there was a condor sitting below us on the cliff. Herrera looked over the edge and said, “Oh, yeah. So if you go over here and look down, you’ll see a big black bird.”

I was surprised. I didn’t expect to see a condor so quickly. Moving to the edge, my eyes scanned the cliffside and rested on a rock. There was the condor, hunched in a black ball. I wouldn’t have noticed it if it hadn’t been pointed out to me.

Huntington explained that I was looking at a male juvenile, part of a family of four birds that patrol the cove below for dead sea lions—or whatever else they can find. Earlier that day, the bird had been chewing on a beer can. Huntington, who is trained to safely haze condors away from danger, sprayed the bird with a water bottle to get him to leave the can alone. “It took a bottle and a half of water before he finally got fed up,” he said.

As we talked, the bird suddenly took off over the cove, flickering like a shadow toward a hilltop. Herrera suggested we might have better luck if we followed, so we piled in our vehicles and drove the short distance to the crest.

As I pulled up, my eyes fell on the metal guardrail running the length of the parking lot. Underneath, I spied a bird’s white foot with long black talons. Hastily, I opened the door and climbed over the railing. There, not 10 feet away, were two adult California condors.

They were large, about the size of turkeys, with long black feathers folding luxuriously around their bodies. From frills of smaller feathers, like Elizabethan collars, came long pink necks and orange bald heads. One condor turned to look at me, tilting its lobster claw of a beak toward the sky. Calmly, it regarded me through a cranberry-colored eye before turning back to the other bird.

“You can get closer,” Herrera said, but I didn’t move, unwilling to disturb this rare sight.

A moment later, a third bird sailed up, landing on a rock. As it drew in its wings, I saw white streaks underneath, like it was wearing a Halloween skeleton costume. Then all three launched into the air, soaring toward the ocean. It looked like they were flying away, but instead they turned back toward us. Between the space of hill and ocean, where we were standing beside the road, the three condors began swooping overhead in long, arching ovals.

We fell silent, awestruck. On the ground, the condors had seemed a little awkward, but in flight they were stunning. The enormity of their bodies was emphasized by long feathers that dangled off each wing like trailing fingers. Huntington later told me that those feathers are as long as my arm. As the sunlight hit the condors, I marveled at how colorful these black birds were—the white on the wings and feet; the orange, yellow, and pink variegation of their heads; the gray of their beaks. They fit in perfectly with this place, a dazzling addition to the scenery. Several times, they passed over my head, their shadows touching me like a blessing.

Finally, the birds flew higher and drifted away. Huntington was elated, explaining that I’d seen something special. “I’ve not had a fine show like that in ages,” he said. “It’s absolutely tops. It was amazing.”

When I asked Herrera what draws her to condors, she started to answer, then teared up and excused herself. To give her space, we averted our eyes in time to see the juvenile from earlier flying above us along the hills. While the younger bird was the same size as the adults, it seemed smaller, somehow, although maybe it was just higher up.

Herrera returned and apologized. Like many people in 2020, she said, she was going through a hard time.

“It’s very emotional, you know?” she said.

“Yes,” I said. “The birds are beautiful.”

“Yeah, and it’s connected to what I’m going through,” she said. “I think of how much time I spent at a young age watching these condors in their habitats. Yes, they’re big, amazing birds, but they have their own feelings and behaviors and connections with each other. And you know, what puts them in danger really sucks, the main cause being lead. It sucks that something can kill such a beautiful animal.”

I told Herrera how the California condor still seemed hopeful to me in this era of bleak news. I want to believe there’s an ecological path forward, even as I know how hard it is to rebuild something that’s repeatedly destroyed. Fire and lead poisoning had reduced the condor population significantly in 2020, but that morning, as we stood in Big Sur with condors sailing around our heads, Ventana had released four new birds into the wild. In December, there would be five more.

“Have you ever been there when they released a condor?” I asked.

“Yeah,” Herrera said.

“What was that like?”

“It’s like saying ‘Good luck,’” Herrera said. “Welcome to the world—you’re gonna love it. Stay away from lead.” We laughed, and she added, “It’s really nice to see that they can have that. They can have the world, like the whole range. They can just be free.”•