Photo: Peter King/Fox Photos/Getty Images

This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

Although COVID has brought an avalanche of new stressors into our lives, it has also eradicated a number of minor ones. For example: the anguish of wondering whether you are dressed appropriately for a social occasion. Social occasions — ha! When this is all over (a clause that, by the way, I first typed one year ago for a completely different article), will anyone remember how to iron a shirt, much less affix a cummerbund?

Well, at least one person will. Dress Codes: How the Laws of Fashion Made History is a new book by Richard Thompson Ford, a Stanford Law School professor who has terrific personal style. This is an irrelevant biographical detail for most academics but a qualification here. Ford is not only a decorated scholar and fashionisto but a Best Dressed Real Man, as we learn in the book’s introduction. In 2009, Ford writes, he entered Esquire’s Best Dressed Real Man contest on a lark. His second child was 10 months old at the time. Family life was a whirlwind of plastic baby toys and diaper changes. It struck him as potentially entertaining to submit himself as “a harried 43-year-old dad versus a bevy of lantern-jawed aspiring actors, sinewy fashion models, and athletic-looking frat boys.” The contest winner would receive an all-expenses-paid weekend in the Big Apple. One of the submission photos, reproduced in the book, depicts Ford in a blue pinstripe suit with a squirming infant in his lap. To his own astonishment, he made it to the semifinals before being eliminated in favor of the ultimate winner.

But the joke is on that guy, wherever he is, because he didn’t go on to write a 464-page survey of Western fashion legislature with full color inserts and sections like “Hip Hijabs” and “Decorative Orthodontic Devices (a.k.a. Grillz).” Ford was also probably the first to offer a detailed analysis of Donald Trump’s “disturbingly long” neckties, which he published a few years ago in op-ed form as a kind of sneak preview of this book. In the opinion piece, he outlined the aesthetic felonies of Trump’s accessory: too shiny, improperly knotted, and misassembled so that the short end couldn’t properly moor in its loop and was instead doomed to flap in the breeze. The piece made strong points. Nothing about a president should “flap.” The overlong tie, Ford argued, might even constitute a sort of fraud; after all, in Renaissance England, a man caught overstuffing his codpiece was forced to march through the streets with the stuffing pulled out as a public admission of stealing penis-size valor.

The joy of Ford’s book comes from learning about all the things people have historically been banned from doing to or with clothes. And by banned I don’t mean that a gauzy societal opprobrium might have descended if you stepped out in the wrong “payre” of pants but that a Scottish man who wore a kilt in 1746 could be tossed into prison (no bail) for six months. Governing bodies absolutely live to sweat the small stuff.

Those bodies are no longer determinant forces of how we dress. During COVID, the tacit guidelines for dressing — the ones that deal with coolness or professionalism or gender — have disintegrated even further, opening a wormhole into realms of unprecedented sloppiness, eccentricity, discovery, and creativity. There has likely never been a point in U.S. history when the populace has spent so much time being unobserved by the public. You may have experienced this as a relief, or you may have experienced it as a loss.

I know that my inability to observe the self-ornamentation of others in real time over the past months — the stark removal of people watching as an available activity — has turned down all the saturation levels on life. There was a lady in my old neighborhood who was entirely green, for example. Green hair, green clothes, green accessories. Her age: mid-60s? Who knows, doesn’t matter. Nothing about the green goddess suggested that she was enacting Greenness for the pleasure of the world. It was a private quest that only inadvertently revealed itself in the course of her going out to buy milk or hit the ATM.

It is perhaps because I’ve not had access to such people that my own COVID dressing has slipped over the months from adult swaddling clothes into green-goddess territory. In autumn, I transitioned from pants to tights and from tights to sheer leopard-print stockings. In winter, I collected fluffy bits of lichen from the yard and tried to sew them into a wig. (Too crumbly.) Last week, I Googled images of Marie Antoinette with a model frigate woven into her hair and wondered if I could Do It Myself. Without external stimulation, some of us are driven to “be the person you wish to randomly walk past in the world.”

Today, the online Trump Store offers a $125 replica of the tie Ford analyzed. It arrives complete with a “complementary” [sic] gift box. But who is buying ties — jumbo red ones or otherwise — in a pandemic? The past year has scrambled the way we present ourselves. For the nonessentials among us, COVID has done away with dress codes and replaced them with a fashion abyss. We are left with a question that is as peripheral as it is prevalent: What to wear, what to wear? Here, some suggestions:

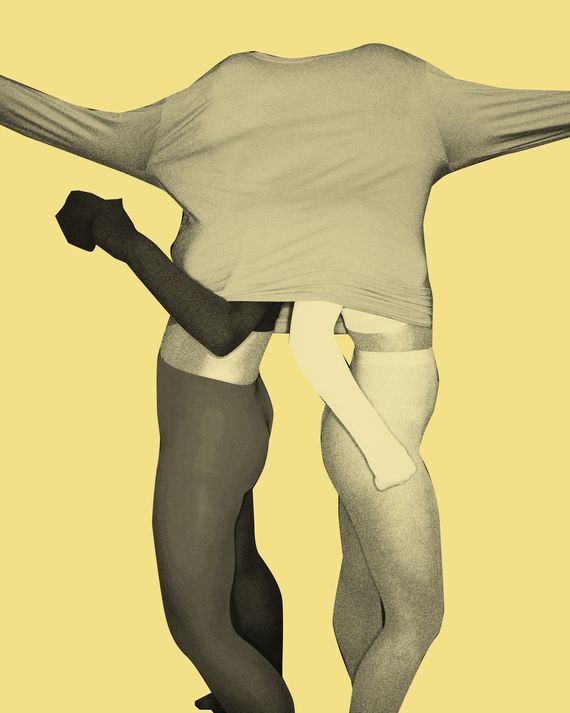

Locked Down is the name of a Doug Liman movie that came out on HBO Max in January. The project was completed entirely during the pandemic and, as Metacritic puts it, received “mixed or average reviews” upon release. I liked it. The genre is “romantic comedy/heist,” and though the sum is less than those parts, the parts are fun enough that it doesn’t matter. The film’s triumphs are its documentations of life under COVID, including what we might now term the Zoom Mullet: Business on top, party on the bottom. In one scene, the high-powered businesswoman played by Anne Hathaway Zooms with her team while wearing elegant earrings, a tailored blazer, silk blouse, and loudly patterned pajama pants yanked well north of her bellybutton. What her team doesn’t know won’t hurt them.

The Zoom Mullet adds both a comedic and an erotic charge to routine digital workplace interactions. Is the person on the other end of the line wearing baggy leggings? Sweatshorts? Tighty-whities? Lacy underwear? No underwear? You’ll never know … and they’ll never tell. Here, we have one method of dressing destined to flourish as long as people continue to work remotely. Dance like nobody’s watching, sing like nobody’s listening, dress like your lower body is invisible.

Photo: Tara Moore/Getty Images

Until the Late Middle Ages, Western fashion moved at a crawl. The general shape of clothes remained the same for decades, maybe centuries. A rich person’s tunic might have been silk instead of wool, and the length might have gone up or down over the years, but it was otherwise a near-identical sack. Most people wore clothes until they were rags. The idea of discarding a piece of clothing because it was no longer cool, rather than no longer functional, was inconceivable. Equally absurd was the idea that you could infer something about a person’s character or taste from his clothes. His rank, yes. His soul, no.

Trade expansion in the 14th century made cloth more widely available to the emergent middle class. This coincided with a dawning sense that a person’s identity might be more tied up with what he did than with how many hectares his dad owned. Selfhood wasn’t preordained after all — it could be constructed piece by piece, with clothing as a tool.

This was immediately recognized by those in power as a problem. Ford writes about a servant in England who was arrested in 1565 for wearing “a very monsterous and outraygeous greate payre of hose.” The pants in question were trunk hose, which are inflated shorts with sewn-in panels that a wearer can yank to puff out the shorts, bullfrog style. The offender was detained and ordered to change outfits, and the illegal pants were exhibited in public so that others could meditate on the “extreme folye” of the servant. “Dressing wrong” in the confines of your house is not a rebellion on the scale of English the servant, but a way to exert deviance without repercussion—a form of self-soothing that every infant with a spoonful of food and a throwing arm understands.

A few years ago, a co-worker pointed out that I had a habit of wearing unflattering colors. She said things like, “It’s not that you look bad in yellow; it’s that no one looks good in it.”

As a gift — and also a remarkable neg — she booked me a color consultation and face-shape analysis. I took a train to see the consultant, who wore jewel-tone fabrics with abundant draping. During the appointment, she held cards to my face, examined me under a white light, and demonstrated how to spread a green paste over my cheeks to deemphasize my rosacea. It was revealed that my color type was Exotic Winter and my face shape an inverted triangle.

I bought the green paste and a booklet of hairstyle suggestions. Asymmetrical cuts, the consultant explained, would correct for the defects of my head shape. Recognizing the undertones of my skin color would have a powerful impact on the choices I made. A wardrobe of flattering hues would bring out my best. Under no circumstances was I to wear brown, orange, yellow, or warm pastels. These days I don’t work at the office with the color-obsessed co-worker — or any office — but I think about her, now and then, when I slip into a forbidden hue.

Photo: Bettmann/Bettmann Archive

Underpinning a law like the one against trunk hose is, of course, an attempt to freeze and control a social order. In 1943, a squadron was dispatched to East Los Angeles in search of Mexican American men wearing zoot suits so they could beat up the men and tear off the zoot suits, which they trampled, burned, and peed upon. In theory, the suits were offensive because they used a lot of fabric, which was rationed at the time. It is more likely that the wearing of the suit indicated a sense of self-determination, which poked at a racial hierarchy that looked, increasingly, like the end stages of a Jenga game. Young ladies who wore zoot suits were called zooterinas.

Louis XIV amused himself by inventing rules about who was allowed to wear brocade. The people on the king’s Brocade List included himself and an assortment of people he liked. If a person wanted to wear, say, an embroidered brocade justaucorps with a scarlet sash, he needed to obtain physical authorization from the king. Only 50 people at a time could be on the Brocade List. As soon as one person was cut, there was drama about who would replace him. Today, elite fashion brands maintain similarly strict guidelines about which celebrities they’ll agree to dress on the red carpet. This practice can be weaponized, too. In 2010, a rumor circulated that Nicole “Snooki” Polizzi, from Jersey Shore, had been sent a free Gucci handbag — not by Gucci but by one of the brand’s competitors.

“Sumptuary law” is law that regulates what people spend their money on: Luxury goods, jewelry, clothes, fancy foods … all the fun stuff. But especially clothes. Women were prohibited from wearing multicolored robes in second-century BC Rome. Commoners were banned from wearing fine black sable in 11th-century China. Sumptuary laws exploded toward the end of the 12th century, detonating all over France, Italy, and Spain. Fourteenth-century women living in Siena were not allowed to wear platform shoes unless they were sex workers.

By the 1700s, even youthful America had its own dress regulations, mostly about lace, which was considered one of Satan’s temptations. But above all, sumptuary laws were a way to crack down on social mobility. It’s a lot harder to “fake it till you make it” if you’re not allowed to fake it in the first place. Although they’ve dwindled, sumptuary laws still exist — and when they do, they tend to adhere to a certain pattern. Municipalities in at least seven states have criminalized the wearing of “sagging” pants. In 2008 Abercrombie & Fitch rejected a job applicant for wearing a hijab. (She sued and won.) UPS only relaxed its rules about natural Black hairstyles just last year.

Photo: yacobchuk/Getty Images/iStockphoto

Platform shoes still have sultry connotations, especially the style recognized in modern times as the Classic Stripper Shoe: needle heel, clear PVC straps, dizzying platform of transparent Lucite. You can buy imitations everywhere, but the industry standard might be a model called Adore-708 made by a company named Pleaser that precision engineers its footwear to serve its true functional purpose as a piece of athletic equipment. Everything about the design of Adore-708 is ingenious. The angled toe box makes it possible to rock on your toes without losing stability. The platform creates an illusion of a high arch without requiring a user to actually stand en pointe. Clear straps allow the whole apparatus to serve as an uninterrupted extension of the leg. The transparency of the heel makes it possible to do floor work without scuffing the shoe (because there’s no color to scuff away). And the lining is padded for all-night comfort. It is an object artful enough that the Met has a Pleaser in its fashion collection.

In a 2004 TV special, Chris Rock observed that there’s something about clear heels “that just says nasty.” But why let one man’s opinion get in the way of the perfect shoe? Pleaser is one of very few footwear brands that allow users to have their cake and eat it too: ease and glamour in one reasonably priced package. The pandemic has ushered in a reversion to comfort in all aspects of dress. This is one form that may surprise you.

The fashion critic Cintra Wilson once delivered a piece of (ruinous) financial advice that I’ve never forgotten, which is this: If you find an ideal piece of clothing with a price tag that violates your budget, you should buy it anyway, because otherwise you’ll become obsessed with the item and waste money on inferior replacements for years to come.

“Your subconscious will punish you by turning [the piece of clothing] into a kind of Holy Grail that you will spend the remainder of your wretched time on earth trying to find again,” Wilson wrote, calculating that for every perfect item she’d surrendered, she had purchased six to ten inferior substitutes.

As you’d expect, dark-net markets are full of contraband. Anyone with several hours of spare time can purchase jewels, gold, bank details, ID cards, body armor, weapons, fake documents, malware, every drug on earth, and … fashion. A convincing faux Louis Vuitton duffel bag goes for the crypto equivalent of $75. A Gucci backpack is $164, a Versace sweater $100, an Offwhite hoodie $30, an Hermès belt with box and bag just $54.80 — a discount of 95 percent from the real thing.

In some cases, the customer service from forgers is better than that of the brands they’re ripping off. A few years ago, I went to the (real) Prada flagship store on Broadway and a salesperson told me my arm was too fat for one of the handbags. I left an angry Yelp review. The fake Prada vendors online are extremely solicitous. “We treat every customer as VIP,” one of the more prolific sellers promises. “We want you to be a happy customer.” It makes you think.

Women who wore loose-fitting pants in the 1920s constituted a sexual fetish known in the trade as bifurcation. Magazines depicted women in pants roughhousing, getting spanked, and hiding under each others’ beds. The fetish has long gone extinct — a case of erotic energy being normalized away by the sands of time.

There are 6,497 customer reviews on a pair of shorts with built-in butt pads on the fast-fashion website Shein. The shorts, which cost $13, are one of many available butt-pad options. You can get lace-trimmed shorts, sheer shorts, mesh shorts, shorts in black or apricot, and shorts with convenient detachable pads. The butt-pad shorts are clearly intended as an affordable alternative to surgical intervention, or a lazy person’s alternative to doing thousands of squats, but one off-label use that immediately suggests itself is that of “portable seat cushion.” If we’re ever allowed to board airplanes again, I will take one for a whirl in the depths of economy class.

Comfort shoes are back, baby! Sales of “unapologetically ugly” Crocs (CNN’s words, not mine) soared in 2020 as millions of people realized that the foam-based clogs fell well beneath the Zoom Mullet threshold. Slipper sales surged. Dress shoes plummeted. As Pleasers demonstrate, functionality need not equal clumsiness. But often it does.

A Danish yoga teacher named Anna Kalsø invented one of the definitive styles of the 1970s when she created a sandal with “negative heel technology” — that is, a shoe in which the toes were higher than the heels by 3.7 degrees, which apparently replicated the sense of walking barefoot on soft ground. An American couple visiting Copenhagen in 1969 bought a few pairs and wore them experimentally, then — locating curative powers in their lumpy new footwear — begged Kalsø to let them sell her shoes in the U.S. After evaluating the couple’s astrological signs, she agreed. Similar to the contemporary company Supreme, Kalsø prohibited advertising and relied on word-of-mouth to sell her wares.

On Earth Day 1970, the Earth Shoe debuted Stateside. There were many styles, all globular and functional, and all promoted as a way to straighten posture, improve circulation, clear the mind, and “reduce the aches and fatigue caused by living in a cement coated world.” Kalsø herself had walked 500 miles in her shoes to prove their durability. The shoes were divisive: About 10 percent of users were totally unable to adapt to the height inversion, while others became so committed that they got married in their Earth Shoes. The shoes attracted a crunchy audience and were quickly seen to be co-morbid with things like brown rice and feminism. Still available for purchase, Earth Shoes now come in updated styles — such a leopard slip-on with laser-cut accents.

Even before COVID, comfort shoes would periodically trend. A celebrity would be photographed in Birkenstocks, or a cushioned New Balance would be refurbished as “normcore.” One imagines that people whose livelihoods demand comfort shoes — health workers, the entire food-service industry — view these oscillations, if at all, with one eyebrow elevated.

Photo: Bildagentur-online/Universal Images Group via Getty

The hazmat suit of the 17th century consists of an ankle-length oilcloth or waxed leather cloak and beaky mask with goggles, plus a cane and goat-leather boots. All of these elements served a purpose. The cane was for prodding and examining patients at a suitable distance, taking their pulse and lifting up their clothes to check for inflamed lymph nodes. The coat’s waxed treatment would have repelled loose bodily fluids. Same with the goggles. The iconic part of the outfit, that mask, was stuffed with herbs meant to filter air emanating from the patient and to conceal foul odors. Sometimes the herbs were lit and allowed to smoke out through a pair of nose-holes, which would have made the costume even more terrifying to anyone on the receiving end.

Miasma theory blamed “corrupt vapors” for the spread of disease, which wasn’t true but was based on the (correct) observation that unsanitary conditions sped up transmission. The length of a plague doctor’s coat probably helped repel fleas, too, which were the actual vectors of plague. It was an accident that the look transformed a regular person into an anonymous and bestial spectacle. Even the mask’s beak wasn’t intended to look creepy; it was just a practical design solution for keeping a bouquet of herbs hovering beneath a wearer’s nose all day.

But if the birdlike mask is accidental, it is also the element that glued this costume to our collective image bank and caused it to stick around for so long. We’ve always loved and feared an animal-human hybrid. Centaurs, sphinxes, , minotaurs; Ganesha, Anubis, Pan: They whiz straight past our conscious minds and into a sunken Pinterest board of the id. There are more than ten “plague doctor” costumes available from HalloweenCostumes.com, including a sexy version and one for children. (But, thankfully, no sexy version for children.)

Remember when fashion brands touted the fact that their clothes could go “from day to night”? With a change of shoes, your office-appropriate sheath could metamorphose into flirty cocktail attire. I’m not sure anyone was convinced of this line, but it was a line. Day-to-night dressing.

COVID, of course, has introduced day-to-bed dressing. A large chunk of workers can log off and tumble directly from desk to mattress in their marshmallow-soft sweats and athleisure made of fabrics that can stretch up to 300 percent of their own size. Will the end of COVID spark a resurgence of physically punishing clothes? Will we sprint toward stiletto heels, Spanx, itchy wide-fiber wools, tube tops, and restrictive latex? Could bandage dresses make a comeback? Chafing bustiers? Those A.P.C. jeans that take a decade to break in? Chain mail? Girdles? Hair shirts?

Nudism came to America from Germany during the Great Depression, and perhaps it’s time to reconsider the movement as a rational response to the overindulgences of capitalism. Nudism started as a tendril of a broader (but still niche) response to everything about modernity that obscured a person’s relationship to nature: urbanization, consumerism, industrialization. Being naked, the German thinking went, exposed a person to the healthy healing powers of sun, light, and air. It was hygienic. It aimed to unravel the shame that society had insisted on attaching to the body. It was an ideal and a therapy — and, to this day, arguably the only fashion choice immune to being commodified or appropriated. If style wars are class wars, could nudity be the future of resistance?

Five years ago, I was walking north on Bowery when I paused at a red light behind a slight young woman in a faux-leather jacket and sunglasses. It turned out to be the actor Rooney Mara. As we waited for the light, I noticed that a raw egg had been broken against the shoulder of her jacket and allowed to slightly calcify. The light changed and Mara strode forward, while I paused to examine the situation. How had the egg gotten there? It was not in a place where an egg might have naturally fallen over the course of being eaten. Also, the egg was raw. Had someone thrown an egg at Rooney Mara? Had she thrown an egg at her own jacket? Either way, why? She clearly knew the egg was there — it glistened, unmissable — and, equally clearly, didn’t care.

The purpose of clothes is to cloak our private parts and protect our bodies from hailstones and heat and the world’s millions of species of insects. The effect of clothes, which isn’t so simple, is what we call fashion. For a certain kind of person, the Mystery of Rooney Mara’s Jacket is exactly the appeal of it. An outfit is a crossword puzzle: The clothes are clues; the solution is the person wearing them. Sometimes a puzzle is booby-trapped with tricks and fake-outs, which can either be deciphered exegetically or abandoned in bewilderment.