Arturo Cuenca updates

Sign up to myFT Daily Digest to be the first to know about Arturo Cuenca news.

In the late 1980s, Arturo Cuenca had an argument with Fidel Castro and the Cuban communist party’s chief ideologist, Carlos Aldana. Cuenca, then in his mid-30s, was already an acclaimed artist. The setting for their showdown was a gathering of the National Union of Cuban Writers and Artists, Havana’s central office of officially sanctioned culture.

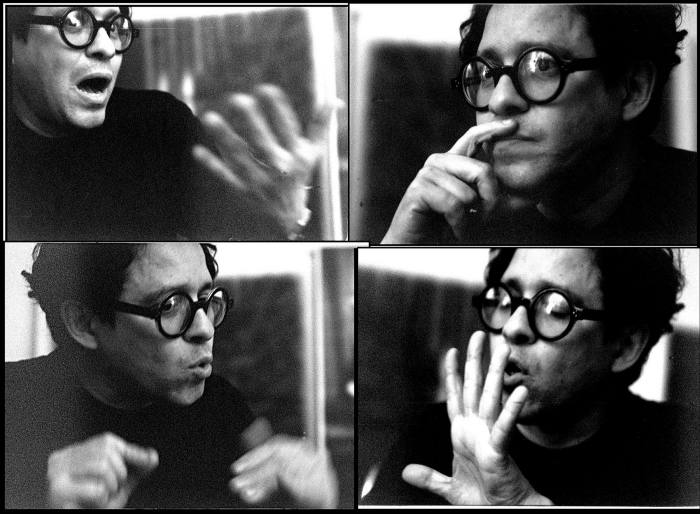

Cuenca, the conceptual artist who died in Miami this week aged 65, opened his speech with a vote of thanks. The revolution, he told the audience, had provided his generation with boundless opportunities. He himself was a model of Marxist creation, steeped in Hegelian phenomenology. For that reason, Cuenca continued, it was time for the old guard to listen to the young — and step aside.

Aldana was left speechless. Castro was infuriated. “Who is this Chinaman anyway?” he commented, using a colloquial put-down of the time.

Cuenca became a cause célèbre, especially among the young, and was ultimately forced into exile. In July this year, artists calling for free speech sparked Cuba’s biggest street protests in living memory. After Cuenca’s death they circulated a 1980s video of him painting, dancing, playing chess, and of course talking. “The vanguard always needs a way out,” he says at one point.

Arturo Cuenca Sigarreta was born in the province of Holguín in 1955. His absent father was an engineer in a sugar mill, and he was raised by his deaf-mute mother, a former member of Castro’s 26 July rebel movement.

Cuenca won a place, aged 18, at San Alejandro, Cuba’s most prestigious art school, shortly after his mother moved to Havana. But he soon dropped out and moved to the literature department at the National School of Art Instructors. There he became a popular mentor to a band of students-cum-acolytes, drawn to Cuenca’s genius and flamboyant style. Defying drab socialist mores, he cut their hair into Japanese style geometric bobs, and redesigned Soviet-made trousers with exploding seams. He called them “pants that dream of becoming pantaloons”.

Like everyone who ever met Cuenca, I count myself lucky to have known this independent spirit imbued with Caribbean duende who was enthralling, witty — and infuriating. “I am the most famous artist you have never heard of,” he would say.

He called his elegant paintings, which mixed photography with text to create pale and often blurry images that recalled the work of Gerhard Richter, “palimpsests”. One famous image from the late 1970s shows a woman’s face with her mouth rubbed out. A clear reference to censorship, it now hangs, ironically, in Havana’s Bellas Artes museum. In 1980, aged 25, Cuenca had his first international show at the Paris Biennale.

“Cuenca’s work was fundamental because he transplanted conceptualism and post-Modernism from the outside world inside Cuba,” Rafael Rojas, one of Cuba’s leading intellectuals told me. “The importance of his work was thanks in great part to this cosmopolitanism.”

In 1991, soon after his confrontation with Castro, Cuenca moved to Mexico City. There, with Nina Menocal, an aristocratic émigré, he co-founded NinArt which provided an important platform for other now famous Cuban artists of his generation, such as José Bedia and Tomás Sánchez. But it was in New York City — or New Work City, as Cuenca called it — that he found a second home.

His third floor walk-up in Manhattan became part salon, part crash pad and part dance hall for visiting exiles. The bathroom was also his darkroom. The music and conversation there was very Cuban — which is to say, very loud. “In the Tropics, even ideas dance the guaguancó,” he liked to say.

Cuenca had many solo shows and won prizes, including the Cintas prize in 1992. Yet he never quite penetrated the big leagues of New York’s art scene. Cuenca blamed the city’s leftist intellectuals, accusing them of being in cahoots with Havana. No doubt his difficult personality did not endear him to gallery owners. Perhaps his poor English did not help either — although there was a genius to that, too. Cuenca, always frugal, loved thrift shops and would marvel at how the word “thrift” was “so difficult to pronounce”, with just one vowel “lost among those skyscraper consonants.”

Shaken by the events of 9/11, Cuenca moved to Miami. Short of funds, he paid for everything — including dental work and car repairs — with art. Like many Cuban-Americans, his politics became Trumpian. Yet he never lost his flair, love of life and enjoyment of kabuki theatre, Marcel Proust and Oscar Wilde. His simple message the last time we spoke was: “Beauty is free.”

The writer’s most recent book is ‘Solitude and Company’